Frederic Leighton's views on race

What evidence survives today to inform us of Leighton's attitudes to people of other ethnic backgrounds? The Arab Hall within his home at Kensington would seem to testify that he had a great love of Middle Eastern cultures. Records also prove that he had amassed an enormous collection of Japanese and Chinese objects, textiles and artefacts over his lifetime. Leighton might also have been conscious that as a result of his continental up-bringing, he himself was not seen by some of his contemporaries as being 'fully British'. His first biographer, Emilie Barrington wrote in 1906 'certain Englishmen who knew Leighton had difficulty in recognising him as one of themselves'. More disturbingly, Barrington also mentions that the famous nineteenth-century author and cartoonist George du Maurier was 'convinced that in Leighton existed indications of foreign or Jewish blood but was quite unable to discover any facts in support of this theory and was troubled on this point'.

Leighton's personal letters

There are numerous letters written by Leighton to members of his family that describe African peoples in extremely disturbing language. In fact, Leighton frequently distinguishes in his letters his liking for Arabic cultures over African - this being connected to the prevalent notion of 'hierarchy of skin colour' in the nineteenth century. When referring to Middle Eastern customs he states

'Eastern manners are certainly very pleasing, and the frequent salutations, which consist in laying the hand first on the breast and then on the forehead, making at the same time a slight inclination, are graceful without servility'.

In contrast, his statements about Africans are very different. It is a sad fact that over half a century following the abolition of slavery in Britain in 1807, Leighton and his contemporaries were still describing African people in the same dehumanising language of earlier times. While politics might have moved on, popular perceptions of Africans had not. (See previous essay 'Attitudes to Race and Ethnicity in the British and Ottoman Empires' for reasons for this). The issue of slavery is something that Leighton witnessed personally in Egypt in 1868. In one of his letters he describes coming across a party of young African slave girls. The trade in African slaves to the Middle East had taken place for centuries and was still an enormous business for the Ottoman Empire at the end of the nineteenth century. Leighton wrote of the encounter

'I saw during my evening stroll and for the first time in my life, a group of slaves, mostly girls. If I had seen them subject to any ill-treatment I should have felt very indignant; but I am bound to own that, seeing them squatting around a fire like any other children, showing no mark of slavery, and occupied in cooking their food, scratching themselves, as well no doubt they might, and looking otherwise very like monkeys, I found it difficult to realise myself the hardship of their position, however much it may revolt one in the abstract'.

It is clear to see in this extract, that while Leighton appears disturbed by slavery itself, he cannot seem to feel real empathy with the captive African girls. How do we judge the character of a man who would have no understanding of a twenty-first century definition of racism? What is beyond question is that the continued dehumanising of African peoples over the course of the nineteenth century allowed European nations to absolve themselves of their guilt in what became known as the 'Scramble for Africa' and its colonisation by the end of the century.

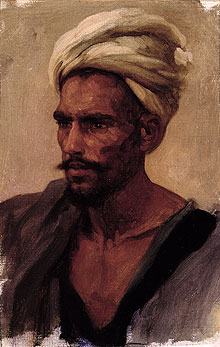

Leighton the Orientalist

If the word 'orientalist' is taken to simply mean someone having an interest in the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East and Asia, then Leighton can be called an orientalist. However, for most people today orientalism is not as simple as the above definition. It raises much more complex issues around the themes of imperialism and biased Western views of the Middle and Far East. In 1978 the academic Edward Said published his ground breaking book 'Orientalism; Western Conceptions of the Orient'. Said's main argument was that from around the year 1700, Europe started to form stereotyped views of the world that existed to the east of it. In Said's view, historians, philosophers, writers and artists all added to these overwhelmingly negative views, for example, a belief that eastern societies were backward and in need of European assistance to develop. Said's conclusion is that orientalism as a subject and way of thinking paved the way for European states to colonise the East. Said's view has since been criticised by academics such as Robert Irwin and John M. MacKenzie who state that it is incorrect to view Europe's relationship with the East as purely one of aggression and colonisation. They point to the cross fertilisation of ideas between cultures and the enormous influence of eastern cultures on the West. Leighton's Arab Hall would certainly fit into this category.

Documents and Sources

>Letter from Leighton

> Letter to Leighton

> Leighton's Tangiers

> Empire and Travel Map

> Collecting Map

> La Zisa Palace

> Leighton's Paint Box

Who ruled the Middle East in Leighton's time?

Who ruled the Middle East in Leighton's time? Where did Leighton travel to?

Where did Leighton travel to? What did Leighton collect during his travels?

What did Leighton collect during his travels?