Q&A: The Arab Hall at Leighton House

Learn more about the most iconic room of Leighton House with expert Melanie Gibson.

The Arab Hall at Leighton House is for many the centre piece of this unique artist home. Started in 1877 it was not fully completed until 1881. An extension of the original building, it reflects Leighton’s personal fascination with the Middle East which he often visited on his travels.

Widely admired by Leighton’s contemporaries, the Arab Hall’s fame and reputation continue to the present day, as a favourite spot for visitors and much sought-after location for photoshoots, films and music videos.

Find out more about this iconic space and read our Q&A with Islamic Art expert, Melanie Gibson.

The inspiration and design

What was Leighton’s inspiration to build the Arab Hall?

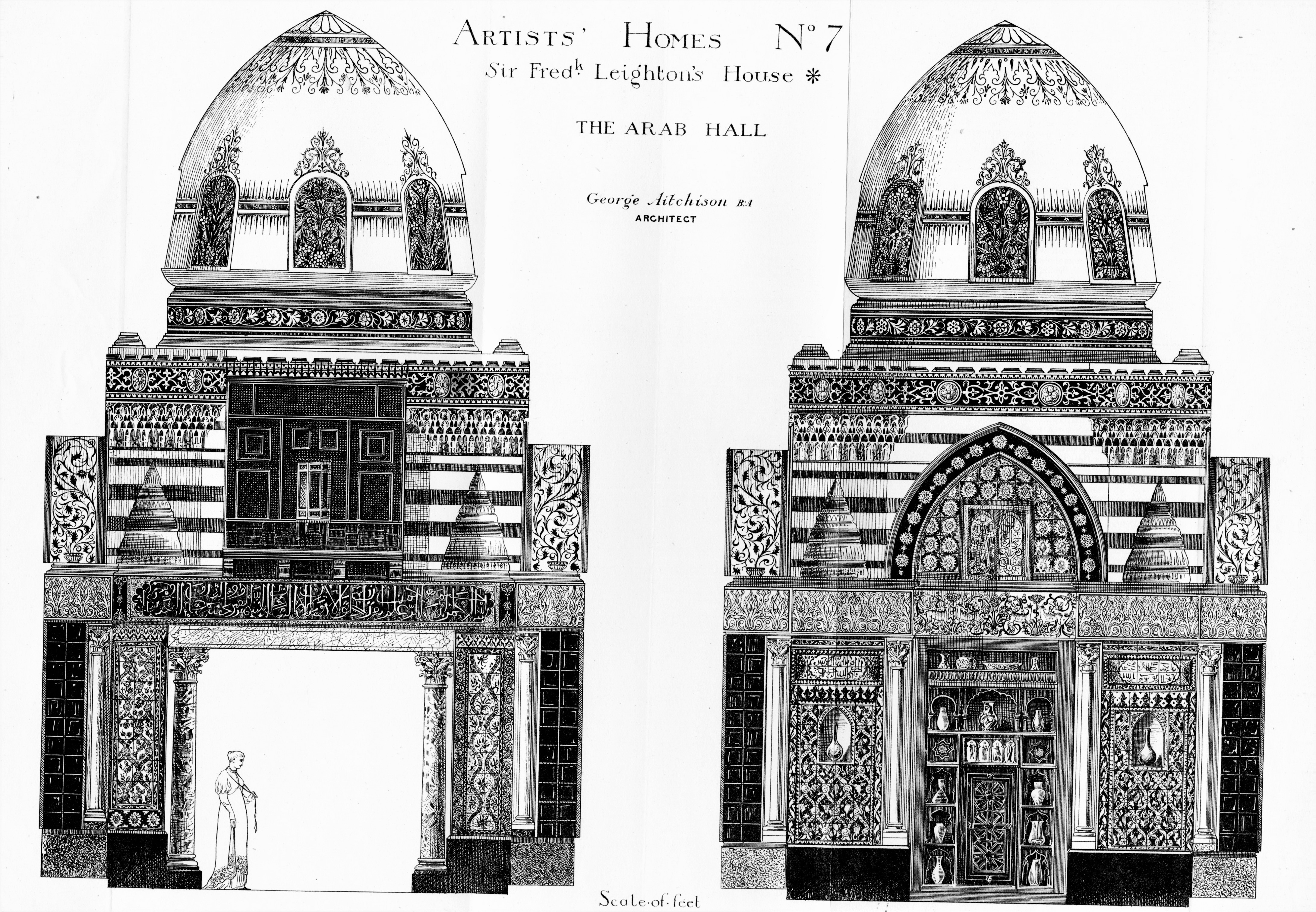

Leighton worked closely with his architect George Aitchison. They were inspired by different buildings that they admired on their travels to Palermo, Granada, Istanbul, Cairo and Damascus.

How many initial plans were there before the final design was realised?

There are several coloured drawings made by George Aitchison of how he planned the tile panels, but none match the final design.

How much did the Arab Hall cost to build?

It is possible to piece this together from Leighton’s bank account at Coutts and includes Aitchison’s fee as an architect, it came to more than £7,000. The original house had cost just £4,500 to build, which demonstrates what an expensive undertaking it was.

Does it require specific conservation treatments?

The Arab Hall requires plenty of conservation cleaning – in particular the wooden screens (known in Arabic as mashrabiyya) get very dusty. There are sensors in the room that keep tabs on the temperature and humidity as well.

What is that small shape at the very top of the exterior of the dome?

The exterior of the dome has a metal spire topped by a crescent which is typically found on the domes of mosques and shrines in Egypt, Syria and Turkey.

Did Leighton use the Arab Hall as a setting for any of his paintings?

Leighton only used the Arab Hall as a setting for one painting called 'Sun Gleam' which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884. Two paintings dated 1877, the same year the construction of the Arab Hall began, ‘At a Reading Desk’ and ‘The Music Lesson’, feature furniture, textiles and carpets that he bought on his travels in the Middle East.

Does the Arab Hall reflect Leighton’s persona or his arts?

Some 19th century visitors described the Arab Hall as an exotic space from The Arabian Nights but Frederic Leighton once referred to it as ‘a little addition for the sake of something beautiful to look at once in a while’, a light-hearted comment that emphasises that he considered the beauty and harmony of his Arab Hall to be its essential qualities.

Wooden screen or mashrabiyya in the Arab Hall, Leighton House.

Arab Hall, grape tiles, Leighton House

Middle Eastern tiles

Did Leighton design and have the tiles produced specially or did he have them brought from the Middle East?

Leighton collected and purchased many of the tiles himself on his trips to Turkey, Egypt and Syria, as well as asking friends and colleagues to acquire further tiles for him. Caspar Purdon Clarke, who went on to became director of the V&A museum in London, purchased the two matching panels featuring grape motifs on the West wall, in Damascus in 1877.

How were the tiles transported from Syria to London?

Leighton travelled to Damascus in 1873 by ship to Beirut, followed by a diligence (stage coach) which took 13 hours. He would have brought back his purchases, carefully packed in wooden crates, in the same way.

How long did it take Leighton to source the tiles?

We don’t know exactly when Leighton started buying tiles, but it may have been on his 1867 trip to Turkey and Greece. We know that he bought a number of Iznik ceramic plates in Lindos in Rhodes on this trip – these were subsequently hung on the walls of his dining room. He probably bought some tiles while on a trip to Egypt in 1868 and many more while visiting Damascus in 1873. His friend William Wright whom he met on his trip, talks of hunting for 'tiles and plates' with him in the city. The building of the Arab Hall was mostly finished in 1880 by which time all the tiles were probably in place.

Examples of tiles in the Narcissus and Arab Hall, Leighton House.

Was William De Morgan involved in the design of the tile panels?

Assembling and arranging the different tiles to create a coherent and harmonious whole was a feat requiring considerable skill and Frederic Leighton and George Aitchison commissioned William De Morgan, an experienced ceramicist who had opened his own studio at 36 Cheyne Row in 1872, to make repairs to the damaged tiles and replacements for the missing ones. De Morgan also created the beautiful deep turquoise tiles which line the walls of the Narcissus Hall and staircase.

Revival mosaics

Who designed the mosaic floors?

The mosaic floors are in the three connecting halls on the ground floor. The black-and-white classical patterns, each one different, were designed by George Aitchison, probably inspired in part by floors he had seen in Italy. In the Arab Hall, the interlinked flower motif border may derive from mosaic decoration in the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem.

Details of the Arab Hall mosaic floor

What inspired the gold mosaic frieze?

Leighton is likely to have seen a gold mosaic frieze at a 12th century palace in Palermo called La Zisa; he visited the city in 1875. The artist Walter Crane whom he commissioned to design the frieze for the Arab Hall mentions being sent a photograph of La Zisa’s mosaic frieze to demonstrate the type of design that he was being asked to produce. The glass mosaic pieces were made in Venice by a firm called Salviati & Co.

Detail of the mosaic frieze by Walter Crane in the Arab Hall, Leighton House.

A calming fountain

Were the fountain and chandelier also brought back from Syria? And how were they installed?

The fountain and the chandelier were both made in London. The fountain had a central jet that splashed into the basin and was originally made of white marble; this was eventually replaced with black marble and had goldfish swimming in it. The chandelier was copied from those seen by Leighton in buildings in the Middle East: he made a drawing of a light fixture in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus. Made by the London firm Forrest and Son, it originally used gas, and was converted to electricity in the 1890s.

Does the fountain still work?

The fountain was originally fed from a water tank on the flat roof above the Silk Room, working by pressure. It was modified twice and eventually the fountain was sealed and converted to an electrical pump because the water appeared to be draining into the foundations of the Arab Hall.

Have many people fallen in the fountain?

There is an account written by one of Leighton's friends, that after a dinner party one evening, while they were drinking coffee and smoking in the Arab Hall, one of them stepped right into the fountain, disturbing two of the goldfish! This even happens today from time to time as visitors look upwards as they walk into this stunning space.

Dr. Melanie Gibson is Executive Trustee of the Gingko Library and Editor of the Gingko Art Series. She convenes the Islamic Art module of the Postgraduate Diploma in Asian Art at SOAS and was formerly head of the Art History department at New College of the Humanities, London. Since 2005 she has lectured on the ceramics and glass of the Islamic world for SOAS, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Courtauld Institute and the Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar. Her research focuses on the ceramics and glass of the Islamic world as well as the reception and use of Islamic pattern in 19th-century British design. Her most recent publication is a chapter on the ceramics of Iran in Bestowing Beauty: Masterpieces from Persian Lands (Yale, 2019).