History of Leighton House

Discover how Leighton's home came to embody the idea of how a great artist should live.

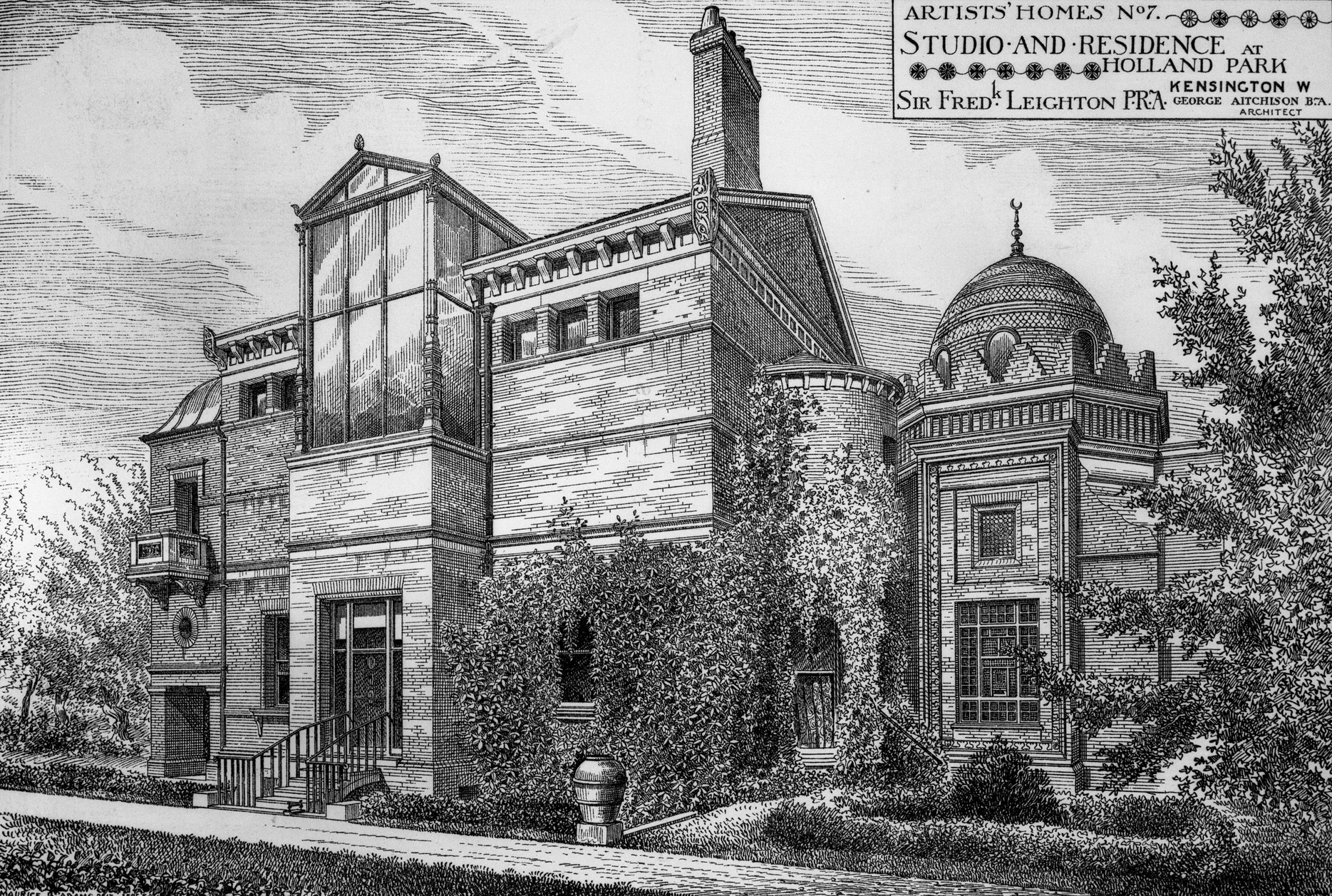

The former home and studio of the leading Victorian artist Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-1896), from its first construction in the 1860s up until shortly before Leighton’s death, his studio-house on the edge of Holland Park was a constant preoccupation. Absorbing large amounts of his time, money and effort, the house combined spaces for living, working and entertaining and the display of Leighton’s collections. Regularly featured in the press, his home came to embody the idea of how a great artist should live.

Studio-house to private palace of art

Leighton acquired the plot for his house in 1864 and began making plans for its construction. For a number of years, he had harboured the idea of building a purpose-built studio-house and had an 'old friend' in mind to act as his architect.

Leighton's architect

Leighton first met George Aitchison (1825-1910) in Rome in the early 1850s. He was the son of an architect and the family practice had specialised in wharves, warehouses, docks and railway architecture. When Leighton commissioned him, Aitchison had designed no houses and would be responsible for just a single further example. Nevertheless, his involvement with Leighton’s house extended over 30 years and changed his career. Through his work for Leighton (which included interior design and furniture design) Aitchison was engaged by a series of wealthy and artistically-inclined clients to remodel and decorate the interiors of their London homes. Sadly, very little of this work has survived and Aitchison's reputation has largely gone with it. But as both Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy and President of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Aitchison was a prominent and respected figure in the architectural world of the late nineteenth century.

George Aitchison.

The first phase of construction

Work started on the house in 1865 and continued while Leighton took an extended tour of Spain. In October he was in Rome and was able to move in on his return. Externally, the new house was strikingly plain, with little ornament or embellishment. The south facade, facing the street, was given the appearance of an Italian palazzo. The north facade overlooking the garden was dominated by the large studio window on the first floor. Internally the house was relatively modest at this stage, consisting of just a dining room, drawing room, breakfast room and staircase hall on the ground floor. Upstairs were just two rooms: Leighton’s great painting studio and his surprisingly modest bedroom.

'He built the house as it now stands for his own artistic delight. Every stone of it had been the object of his loving care. It was a joy to him until the moment when he lay down to die.'

The first extension: 1869-70

Within three years of the house being completed, Leighton undertook the first of what would be a series of extensions and alterations. To increase the size of the studio on the first floor, the east wall was taken down and the house extended by some 5 metres. The extension incorporated a new canvas store accessed via a trapdoor in the floor of the studio and changed the way the models entered the studio via the service staircase.

The Arab Hall extension: 1877-81

Leighton often travelled and on trips to Turkey in 1867, to Egypt in the following year and to Syria in 1873, he collected textiles, pottery and other objects that were later to be displayed in his house. However, the trip to Damascus in 1873 laid the foundations for the wonderful collection of tiles that line the walls of the Arab Hall extension. Further examples were collected for Leighton by others, including the explorer and diplomat, Sir Richard Burton. In 1877, Leighton began the construction of the Arab Hall. This was an ambitious and costly undertaking. The main inspiration was an interior contained in a 12th-century Sicilio-Norman palace called La Zisa at Palermo in Sicily. Aitchison and Leighton brought together a group of their contemporaries to contribute to the project; the potter William De Morgan, the artworker Walter Crane, the sculptor Edgar Boehm and the artist and illustrator Randolph Caldecott were all involved. The mosaics and marbles and skilled craftsmen were all sourced in London, although Crane’s design for the gold mosaic frieze was made up in Venice and shipped to the site in sections. The collection of tiles, mostly from Damascus and mostly dating from the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century are as important as any collection of tiles held in the UK.

Arab Hall, Leighton House. Image courtesy of Will Pryce.

The winter studio: 1889-90

The problem of winter smogs and fogs was a concern for many artists whose year was focussed on the submission of their work to the Royal Academy at the end of March or early April. Leighton’s solution was to commission a large winter studio to be added at the east end of his main studio. Glazed on two sides and with a glass roof, the winter studio was supported by pairs of substantial cast iron columns.

The Silk Room: 1894-5

The last addition to the house was completed only in the months before Leighton’s death. Built on the first floor of the house, on what had previously served as a roof terrace, the Silk Room was designed as a picture gallery to house Leighton’s expanding collection of paintings by his contemporaries. The walls were lined with a green silk and the artists represented included many of the leading painters of the day: Albert Moore, John Everett Millais, George Frederic Watts, John Singer Sargent and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

The Silk Room, Leighton House.

House to Museum

When Leighton died in 1896 his collection was sold off at Christies and dispersed. The house however was retained and in 1900 it was opened as a museum and run by a committee led by Leighton’s neighbour and biographer Emilie Barrington. Initially the focus of the displays was works by Leighton, in particular a collection of around 700 sheets of his drawings, which Leighton’s sisters helped the museum acquire. Barrington also donated a number of works to the museum including landscape sketches, and the painting of a Venetian Doge by studio of Domenico Tintoretto which now hangs in the Entrance Hall.

Entrance Hall, Leighton House. Image Dirk Lindner

20th century additions

In 1927 ownership of the house was transferred to The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and the council continue to manage Leighton House today. Around the same time, a local family called Perrin donated money for a new exhibition space, designed by Halsey Ricardo, to be added to the house. The ground floor of this new addition was used variously as a venue for the theatre museum, a children’s library and most recently staff offices. In the 1950s a further addition was made, infilling the space underneath the Winter Studio to create facilities for the children’s library. The upper floor of the new wing is still used as one of the museum’s exhibition spaces.

Closer to Home 2008-10

Throughout the 20th century the identity of the museum changed from being Frederic Leighton’s former studio-home to being a venue for a more general borough museum and events space. In the process, many of the interior fittings and finishes were lost. This coincided with a period when interest in Victorian culture was at a low point.

In the 1980s Stephen Jones was appointed curator of Leighton House and began the process of restoring the interiors. The 2008-10 Closer to Home project continued this, redecorating the spaces based on historic accounts and photographs and returning items from Leighton’s original collection to the house. This included reguilding the dome in the Arab Hall, recreating the original flock wallpaper in the Dining Room and restoring the ziggurats on the roof of the Arab Hall.

Hidden Gem to National Treasure 2019-22

In November 2019, Leighton House began a major project to refurbish the twentieth century additions to the museum. In the Hidden Gem to National Treasure project these spaces were redeveloped and opened up to the public, creating new visitor facilities including, a new ticket office / shop, café, additional display space, step free access to all floors of the building, a purpose-built collections store and a dedicated drawings gallery and learning centre.

By moving visitor facilities out of the historic house, the museum was also able to re-present Leighton’s historic Entrance Hall and Winter Studio, returning them to how they appeared during Leighton’s lifetime.

Exterior of Leighton House. Image Dirk Lindner